|

The Rise and Fall of Roadside Magazine |

|

|||||||||

|

Chapter 11

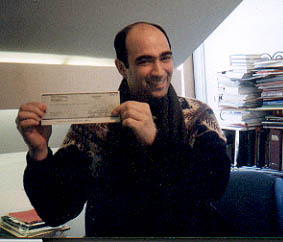

Ten years of effort rewarded with the equivalent of the price paid for a good used diner. (Photo by Marijo McCarthy)

Coffee Cup Publishing was not a complex business. It had no stockholders. No real estate. No outside contractual obligations. For the most part, it was me and an increasingly obsolete computer, a catalog of stories, a very small subscriber list, and a good idea. Rather than an attorney, I enlisted the help of my cousin Andrea Graveline an accountant with experience dealing with small businesses. She immediately put this process on a schedule and provided invaluable advice during the rest of this negotiating period that ultimately lasted nine more months. I also retained an attorney at Andrea’s recommendation. Over this time, I found myself a little dumbfounded at the legal force Mr. Ball brought to bear to acquire my little magazine. The apparent lack of good faith and the obsessive ass-covering of his finance director and attorneys concerned me profoundly. I nonetheless accepted this as a basic fact of doing business and an example of why everyone hates lawyers. From my perspective, we could have sealed this deal with a simple two-page agreement and a handshake, but instead I confronted a non-compete clause, the contract’s governance in Illinois, a paranoiac non-disclosure clause, and an employment contract watered down to effectively mean nothing. Looked at in stark terms, I realized that Ball sought to lay claim to everything I created over the past decade for the price of a good used diner, while giving them the option to kick me out in year’s time – maybe less. It dawned on me that I could alternatively wipe out my debts by declaring bankruptcy, which might destroy my credit rating, but I’d at least have all my stuff. When I realized that George Ball offered me the near-equivalent of a Chapter 11 filing in exchange for ten years worth of toil, I found myself worrying to the point of illness. Though I was nearly desperate to get out of debt once and for all, I just as desperately wanted to see Roadside have its shot at the big time, and I wanted my finger on that trigger.

The entrance to Ball Publishing's offices in Batavia, Illinois during my first visit in December, 1999. The site of this historic mill building raised my hopes that Roadside had landed in good hands. In the December of 1999, still a month before we ultimately came to terms, John Martens invited me out to Batavia for the first time, sending me a plane ticket and a car rental reservation. I landed at O’Hare and picked up my brand new Mustang, and for the first time drove out into Chicagoland suburbia. Previously, Martens had assured me that I’d love the Ball Publishing offices, located in an historic mill building along the Fox River. The setting of Roadside’s possible new home did put me at ease. Batavia is the picture of small-town Midwestern America. The company’s 30 or so employees all greeted me with expected cordiality, with most expressing excitement at the prospect of seeing Ball Publishing branch out of its stable of agricultural trade titles. Of course, everyone there loved diners, though no one at that office had ever knowingly stepped foot in one. “We always try to find the local places,” I typically heard. At dinner, I experienced the joys of the executive expense account. Roadside might be about diners and mom and pop places, but during that visit, Martens first exposed me to his propensity to dine at upscale European restaurants. These people knew how to live, I thought, or they certainly knew how to spend Mr. Ball’s money. No one had ever wined and dined me quite so much.

During this visit, Martens, Mr. Ball, and I began to discuss tentative plans for Roadside’s future and my role within it. I would get a car, they told me, as well as a laptop. I would do a great deal of travel. I would edit the magazine, and I assumed that I would answer to Martens as publisher. But no, they assured, I would not have to move to Batavia – unless I wanted to. Separately, I heard Ball and Martens discuss the working on the business plan. Eight months into negotiations and apparently they hadn’t yet drafted an outline. Yet while the company poured on the hospitality when we actually met, its lawyers handled me like toxic waste. My nagging doubts over the terms of my employment agreement became gut-wrenching anxieties. I didn’t understand why Ball Publishing seemed so intent on protecting itself from me. I attempted to amend the contract. I asked for a one dollar buyout if the magazine failed. No deal. I asked for 10% of the gross future proceeds of any sale of the magazine. They agreed to net. I asked for a clause in the contract that would provide for and insure the necessary resources to conduct my job, like an office and a staff. No. Finally, I asked Martens to explain the point in offering a three-year contract if it was renewable annually. Martens responded with some corporate-speak about protecting the company’s interest. Finally, wracked by indecision, I discussed this matter with my oldest and dearest friend, Julie Rackliffe. In the past, she had advised me against entering into that partnership with Craig and Guy, a previous disaster averted. Now she said, “If it’s making you feel that sick, then just walk.” She was right. I called my lawyer and told her to convey to Mr. Ball that the deal was off. Within two hours, my phone began to ring, and for the first time ever, I felt I had regained the upper hand. I let Mr. Ball hang for twenty-four hours. After returning from a lengthy errand, I found the phone ringing again. Mr. Ball had already left three messages on my voice mail urgently asking me to return his call. This time I picked up the phone. “Randy! What happened? I thought we had a deal?” His astonishment seemed genuine. “George, I’m sorry, but I’m afraid that what you’re offering me just leaves me too exposed.” “Exposed? What are you talking about?” Up until this point, I had actually wondered how much Mr. Ball involved himself with the actual negotiations. I suspected that he left most of it up to Martens and his lawyers. I still saw Mr. Ball as the good guy who delegated authority to those he trusted. I explained to Mr. Ball my misgivings and I also pointed out that he didn’t even have business plan for the magazine, an assertion he vigorously denied. “Of course we have a plan!” he insisted. “Well, what do you want?” he asked. I made a fatal error at this point. I should have hung up and sent him a list of my demands, which I had written down the day before, but I was sick of going back and forth and dealing with lawyers. I just wanted to get this over with. Instead, I winged it and lost resolve. “This employment contract you’re offering means next to nothing, George.” “So you want an iron-clad contract? Okay, how about a two-year ironclad contract.” At the time, that seemed enough. No matter what, I thought, at least I’d get two year’s worth of salary. I longed to rejoin the middle class. I capitulated and signed, and as of February 8, 2000, we were off to the races. George called for a kick-off meeting in Warminster at the Burpee office. When I arrived, eagerly anticipating Roadside’s bold new future, it surprised me to see Jennifer Derryberry also sitting at the conference table. I first met Jennifer last December in Batavia. She also attended the preliminary editorial meetings, where Martens introduced her as merely an interested observer and an outside consultant. Afterwards, I learned that she was also Martens’s live-in girlfriend. When John announced in Warminster that Jennifer would become Roadside’s new publisher, I immediately looked to Mr. Ball for some sign of disapproval but saw nothing. I had no doubt that this perky, 25-year-old had enough talent, intelligence, and drive to promise a successful career in publishing, but I didn’t believe she had the credentials to publish Roadside Magazine. I had, however, little choice but to accept this new reality, and hope for the best. That hope diminished at lunchtime. With Daddypop’s Diner less than a mile away from the office, it was the obvious choice for the kickoff lunch. After we took our seats, I glanced at Jennifer, sitting across the booth from me, and I knew then that I was in big trouble. The expression on her face suggested the palpable discomfort of having a bird plop on her head. The new publisher of Roadside didn’t like diners. Next time: False idols |

| |||||||||

|

©2001 Randy Garbin |